Interview with Nikon Ambassador Joe McNally about his new book, The Real Deal

Search all Robert G Allen Photography articles:

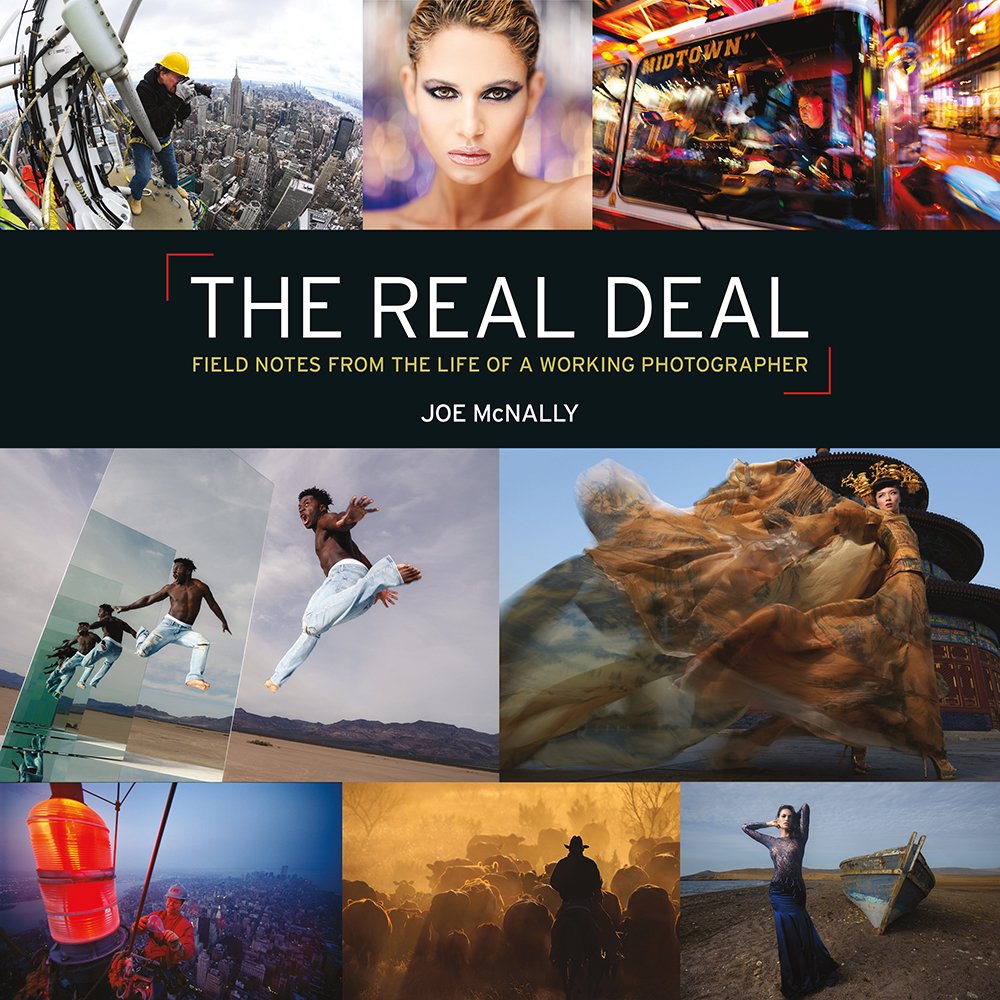

The cover of Joe McNally’s new book, The Real Deal, Field Notes from the Life of a Working Photographer

Robert Allen (RA): Thank you very much for taking your time today to visit with me. I know that your schedule is probably really hectic most of the time.

Joe McNally (JM): It tends to be that way but it's a quiet start to the year. So, if we're going to do anything, this is a good time to do it.

RA: I don't want to go into the typical questions like How did you get started in photography and blah, blah, blah, because I know you've told that story probably 1.2 million times. I'd really like to just focus on your new book.

RA: (But first, I hold up an old Life Magazine with an article containing photos by Joe.)

JM: That's the White House dinner.

RA: Yes. I have that issue of Life from 1990. And to think about that being on film back then. Those photos look fantastic. I also have your latest book right here.

Now, let’s focus on your new book. With your latest book, The Real deal, how did you choose which assignments to write about? That must have been an agonizing process, or are these all of your assignments? It's a very comprehensive book.

JM: It's definitely not all, for sure. There's no absolute method to the madness of writing a book for me, I go with the flow of what I'm thinking about. I generally don't reverse engineer things. I don't say,” Oh, well, people want to know about this. So let me find something to write about that is pertinent to that”. I generally don't do it that way. I come up with a notion or an idea. Sometimes it's even a phrase. And I remember an assignment that addressed that, or there's something in my assignment archive that's in my head that has always reverberated, or I remembered, that draws on the specifics of the job, but also addresses potentially larger issues, like planning, fixers or the thought process of a job or window light, those kinds of topics, which I did cover in the book. It's a phrase that is too often used, that the process is very organic. Everybody says that, but it really is. Maybe a better adjective for me is spontaneous.

RA: When you're writing such a lengthy voluminous book, I'm assuming that the process involves some self-reflection back onto your career. And if that is the case, what have you learned about yourself? Did something pop out about your personality? For example, I can be that way sometimes or I can be this way sometimes?

JM: I did address things at various times that afflict all photographers, you know, stupidity, outright stupidity, occasionally hubris or ego, which can infect the process. And then the notion of durability and being able to withstand the rigors of the field and the kind of reverberation of making mistakes, and coming back from that, and continuing to create good work. And at the end of the book, you look at the kind of life and the photography, you also realize how bloody lucky you are to live a life that has had certainly a measure of interest.

RA: I would definitely agree that it has had a measure of interest. As far as all the various assignments that you've had, I can’t imagine that you would have a favorite one. But do you have one that maybe you remember that sticks out?

JM: There are ones that stick out for various reasons at various times. I've had a grab bag of a career. I have done a lot of different things. It's kept my interest level high because you're always dealing with something new or something different. The overriding kind of aftermath or, again, to use the word reverberation, for me, is what I remember from jobs is certainly the pictures but also mostly, I think, in many, many instances, the relationships and the fact that because I photograph someone that started a relationship, which became a friendship over time, or a return visit over time, where I photographed that same person again and continued to build a rapport and a relationship. And that's always a beautiful thing that is a byproduct of photography. I mean it can be mechanical. It can be like, okay, yeah, shoot these pictures. Thank you very much. We're done here. That happens all the time. But when things are really working, and a relationship is being built, there's far more than just pictures transpiring. There's a bond of trust, beginnings of a friendship, etc. And I've been really blessed to have encountered lots of love with talented, wonderful, interesting, charismatic people over time. And they have certainly informed and uplifted my life by virtue of just having visited with them.

RA: As a child, what did you want to be when you grew up? I assume it wasn't what you ended up doing. But did you want to be a fireman or a police officer or something like that?

JM: When I was growing up, I wanted to be Jacques Cousteau. I really enjoyed his stories of his underwater life. And I thought that would be kind of a very cool thing to do, to look at the oceans. But that didn't happen. But an aspect of it perhaps did because when you go down into the deep, lots of folks will take pictures. There's a piece of this documentation of another world or an aspect of the world that is very fascinating. The overriding sense that I got from Cousteau’s books when I was a kid, and it wasn't just underwater stuff, because I read a lot of adventure stuff, epics and fantasies and Jack London and tall tales from the wilderness and all of that. I probably, at least partially, in response to books that I liked, developed an active imagination.

RA: After 40 years, what continues to inspire you?

JM: Photography is a very durable art form, if you will, or a durable art and craft. It retains its importance, and its immediacy, its ability to inform and move people to action and emotion time and time again. I'm a big, big fan and believer of the power of the still photograph. We live in a very video-oriented world, and I'm not knocking video, I think it's a great thing. It's a great storytelling tool. But for me, my own personal emotions and career obviously, and feelings, about the history that we make, as people are the record of our times, it is very firmly rooted in the notion of the still photograph.

RA: With all the different assignments that you've had, how did you decide which ones to write about in your new book The Real deal?

JM: It's not a textbook, I didn't really have a plan. It's not even a how to book, but there's a lot of information in it. And hopefully, that is informative and worthwhile. But it's not a superhighway. There are a lot of photo books out there that are kind of a how to—how to pose someone, how to do certain aspects of Photoshop. You buy that book, and you start on page one and at the end of page 245, you know how to do a specific thing, it's a very straight-line process. This book is more of a country road. It's a meander through the life of a working photographer and the ups and downs and sideways of it. So, to that end, I wrote about stories that were important to me. I reflected on things that seemed to have a resonance that you could draw forward into the high-speed digital era that we are in photographically. So yeah, that was some of the basis for choosing the stories that were important. At that time, with film or Kodachrome, those kinds of tools of the trade and how they might relate to or be part of the path that leads to where we are now. Which is this digital world.

RA: I see that your book was printed in Korea. I know that some photographers will agonize over color accuracy, and they'll want to be on site when the book is being printed to make sure the colors are true and correct. Did you go through that process? Or did you just say, here, print it.

JM: No. My publisher is very good, Rocky Nook. And they are very attentive to detail. But I did not physically go on press, given the rigors of the world that we face right now. The book was shipped to the printer digitally and printed in South Korea. And before the press run was given the green light, a whole volume of proofs was pulled and sent to the publisher and to me. And there was back and forth about the various nuances of reproduction on various spreads. It wasn't a sight unseen process. It was careful and it was deliberate. But I physically did not go on press.

RA: It sounds like you essentially did almost the equivalent of going on press except you just were not on site then.

JM: Yeah, it’s not a deadline item. Oftentimes, editors have a color checker right on the line when things are really moving like at the National Geographic. Back in the day, the Geographic printing plant basically ran 24/7. There were people there checking those runs all the time because this stuff goes into the magazine, gets bound, and sent out into the world. It's a very, very deliberate process but also very fast.

RA: Those were all the questions that I had. Did you want to add anything or do a closing comment?

JM: Sure. I hope that people enjoy the book. As I said earlier, it's not a specific book about a specific aspect of what you need to know as a photographer. It's not about business. It's not about how to light something. There's a lot of information about lighting in there, but the information is presented anecdotally. It's a series of hopefully illuminating fanciful, funny, and true stories.

As a full time Capture One user (no Adobe products for me), I’m eagerly waiting for May 8th, 2025. For that is the date of their new product announcement. I have no idea what features could be announced but if they are saying “Their biggest update ever” I’m assuming it’s going to be truly big.